History

בית העלמין הדתי היחידי של דברצן - בית הקברות היהודי - הוקם במחצית הראשונה של המאה ה-19. בבית העלמין היהודי טמונים מגיני האומה של של מרד "אביב העמים", אשר התרחש בין השנים 1848 עד 1849 וכן החיילים הגיבורים של שתי מלחמות העולם. בנוסף נמצאים בבית העלמין גם קבריהם של יהודים אשר מצאו את מותם בעבודות הכפיה של הצבא הונגרי במהלך מלחמת העולם השניה וגם שלטים וגל עד לזכרם של קורבנות השואה.

Modern heroic plot

The history of Judaism began in the immediate neighbourhood of the contemporary municipality in the second half of the 18th century, in the days when the Debrecen Fair gained recognition as a nationwide significant event. It was Act XXIX. of 1840 that created the opportunity for the Jewish community to move into free royal towns such as Debrecen. Until this legislation entered into force, only those Israelites were permitted to stay inside the town gates of Debrecen – from sunrise to sunset - who came here because of their work, for example peddlers. They were mostly members of the populous Israelite community of the neighbouring village of Sámson (Hajdúsámson). The Debrecen Council Report issued on 27 January 1840 stated that “in accordance with the prevailing local customs, Israelites are not allowed to live here”. Nonetheless the settlement opportunity created by the new law was not initially seized upon by the citizens of Sámson, but rather by those coming from remote areas, even though many Jews already lived in various noble inns leased by Jewish leaseholders outside the gates on Várad Street. The first such permits were applied for about a decade later.

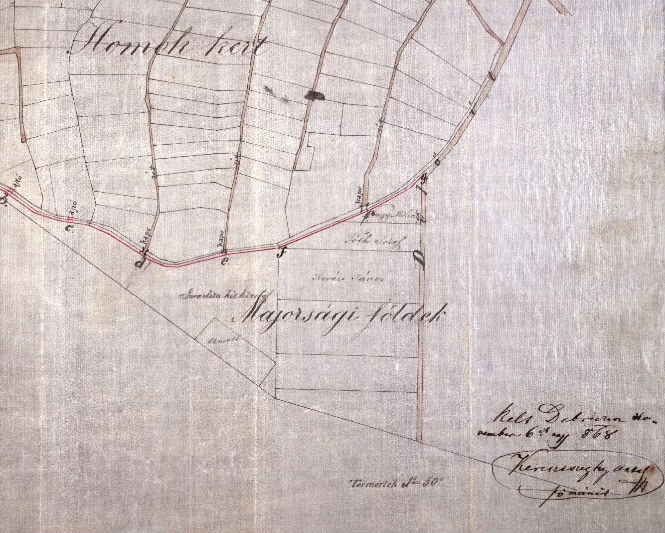

The first cemetery plot and its expansion area in 1868

The first natural sign of finding a home and religious life was the almost immediate establishment of Debrecen’s congregational cemetery. Even though the community of the first settlers consisted of only a few families, on their behalf in the spring of 1842, József Fischer, Henrik Katz, Károly Fried and József Csillag turned with their request to the town’s magistrates’ court to establish a cemetery outside the gate of Várad Street. To support their argument, they referred to an event, namely that in the vicinity of the southwest corner of Homokkert (Sand Garden), a ritual burial had taken place in the previous year at the old cholera cemetery. This is also confirmed by the cemetery records that mention a funeral of a spinster called Rézi Meisel and two other unnamed people from 1841. In accordance with a the decision of the "elected sworn audience and council" of Debrecen, a 200 square fathom (about 712 sqm) area was dedicated for burial purposes on today's Monostorpályi Road, and at the same time the rules pertaining to funerals were stipulated. However, instead of a stone fence, the officials only agreed to the construction of a simple wooden fence, citing the fact that other cemeteries of the settlement were only protected by ditches.

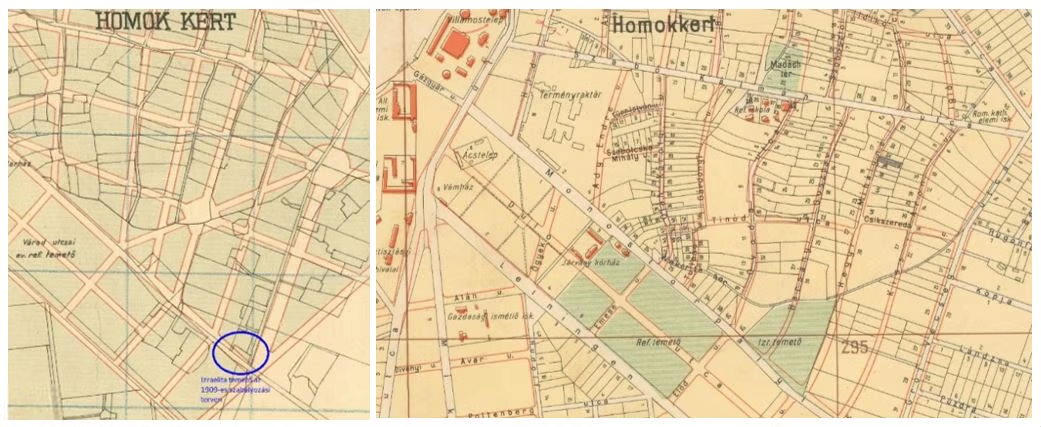

The Reformed Cemetery and the Jewish Cemetery opposite it on Monostorpályi Road around 1880

The Jewish Community of Debrecen, which – due to its strict religious protocols - kept insisting on a solid brick wall, finally turned for help to the Locotenential Council, which finally ordered the town council to comply with the request by introducing a law on 29 July 1845.

The Israelite cemetery on the urban regulation map from 1909

In order to comply with the strict ritual of burying the dead that harked back to Talmud times, the Chevra Kadisa (Holy Society) was founded in Debrecen on 12 April 1852, the statutes of which were ratified in 1877. This organization - which acted in the interests of all the denominations - first expanded the area of the congregational cemetery under their own management in 1855, and later on several different occasions.

The town-owned fenced off property was purchased in 1866, and the ownership rights were registered for the Chevra Kadisa in the land register in 1867.

The cemetery remained an outskirt property until 1897, when due to the increasing population, the area of Debrecen that could be built on was significantly expanded by dozens of gardens outside of the fortification and all the spaces between them, which included numerous working parish cemeteries and abandoned pandemic graveyards. The large-scale urban development concepts of the Millennium included the closing of these cemeteries, and in the long run replacing them with residential quarters. In the preparatory phase of the process that started decades prior to the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, one of the most important projects was to put an end to the general "overcrowding" of cemeteries, and to create a single urban public cemetery in accordance with the legal provisions that re-regulated the burial rules. The permanent members of the committees, which were in charge of the planning discussions, consisted of secular and denominational representatives, including those of the Jewish community of Debrecen. In the recommendation of the committee drawn up in 1913, cemetery sections separated by denomination and independent mortuaries were suggested for the planned new public cemetery. Nevertheless, in the draft finalised by 1915 and submitted in response to a national planning tender, the plan presented by the town's chief engineer contained only one mortuary and a public cemetery not separating denominations. Since the "rotating" grave system included therein was radically different from the requirements of the Israelite religious protocol, the congregation withdrew from the planning process and committed itself to the development of the already existing cemetery in accordance with their own legal requirements. In 1932 when the town’s first public cemetery had finally opened its gates and all previous Reformed and Catholic graveyards were closed, the Israelite cemetery on Monostorpályi Road was allowed to remain open, and it is still the only outdoor denominational cemetery in Debrecen.

The tomb of Lieutenant Antal Spitzer of World War I with Hungarian epitaph

According to the records of the death certificates preserved by the Israelite cemetery on Monostorpályi Road, the nearly 8,000 identified grave sites of the establishment which had been in almost continuous operation for a couple of centuries from 1841, reveal the data of 7,950 people buried there. By browsing among the Hebrew and/or Hungarian epitaphs and engravings of the existing tombs, as well as among the names of the dead listed in the death certificates, visitors to the cemetery and those researching it can find the deceased leaders of the local Jewish congregations and Jewish communities, as well as numerous other significant 19th and 20th century figures. In addition to the political and economic, scientific and artistic elite of the time, Jewish soldiers of the 1848/49 War of Independence are also buried here, as well as heroes and victims of the war and those who died in the Holocaust.

Reconstruction of the labourer's plot and one of the epitaphs in 2013

Even though during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848/49 very few Jews lived in Debrecen, tombs can still be found that depict the eminent defenders of battles.

A significant number of epitaphs referring to the heroes and fallen of world wars I and II can be found in the cemetery. While during the "Great War" the heroic military sons of the Jews of Debrecen were laid to rest in individual or family graves, an independent military plot preserves the memory of the war’s non-local military heroes and prisoners of war who were buried here due to their religious affiliation.

Tomb of a son who died at the Don in World War II and parents who died during deportation. Photography: József Csizmadia

64 of the Jews in the forced labour service during World War II who were executed in October 1944 in the Apafája Forest of Debrecen and buried in a mass grave, were also moved to individual plots and given a final resting place in this cemetery in 1945.

The peculiarity of the Debrecen Cemetery is that it holds countless memorial signs and tomb engravings either on individual or family graves, initiated by the family members of those who were deported or died during the Holocaust. In addition, many memorial tablets or other relics have been moved here from abandoned and closed cemeteries from the surrounding areas of Debrecen.

Just like in any other parts of the world, the distinctive Jewish cemetery on Monostorpályi Road in Debrecen also bears the name "Bét Hácháim", the "House of the Living": the headstones are a link between the dead and the living as long as they are tended to and registered. During the large-scale restoration and rearrangement process of recent years, the plots and resting places of war heroes were the first to be renovated as part of the centenary memorial of the "Great War".

World War I plot in 2019

This time the process covered not only the physical care and settlement of the gravesites and tombs, but also compared the graves’ condition, inscriptions and cemetery records, and their necessary corrections. During the course of the renovation process, the physical and written facts of the cemetery were combined by exploiting the most modern map-based IT. By using the Internet and such developments, it has become possible for anyone in the world to search for and find the data and photos of the tombs of those laid to rest here.

Gallery